As the world’s most complete remains of a Roman palace, Diocletian’s Palace holds an outstanding place in our world heritage. This ancient Roman palace built between ad 295 and 305 at Split (Spalato), at the center of what would become the Dalmation nation by native son Diocletian as his place of retirement after he became the first Roman Emperor to renounced the imperial crown in 305. He then lived at Split until his death in 316 without his wife and renouncing the crown a 2nd time in 308. Diolectan retirement home was as significant as his rule building an imperial city-palace and a sea fortress, as well as a country house of vast proportions and magnificence, covering an area of 7 acres (3 hectares).The Avars badly damaged the palace, but, when their incursion was over early in the 7th century the inhabitants of the nearby ruined city of Diocletian’s birthplace Solin took refuge within what remained of the palace and built their homes, incorporating the old walls, columns, and ornamentation into their new structures. Today this area now comprises the nucleus of the “old town” of Split and Solin has become Solona part of the metro area of Split the largest Croatian city on the coast.The Palace is built of white local limestone and marble of high quality, most of which was from Brač quarries on the adjacent island of Brač which also supplied the stone used to build the White House in the USA. The Palace was decorated with numerous 3500 year old granite sphinxes, originating from the site of the great Egyptian Pharaoh Thutmose III (1479 BC to March 11, 1425 BC) who conquered the Phoenician cities in Syria. Only three have survived the centuries.

As the world’s most complete remains of a Roman palace, Diocletian’s Palace holds an outstanding place in our world heritage. This ancient Roman palace built between ad 295 and 305 at Split (Spalato), at the center of what would become the Dalmation nation by native son Diocletian as his place of retirement after he became the first Roman Emperor to renounced the imperial crown in 305. He then lived at Split until his death in 316 without his wife and renouncing the crown a 2nd time in 308. Diolectan retirement home was as significant as his rule building an imperial city-palace and a sea fortress, as well as a country house of vast proportions and magnificence, covering an area of 7 acres (3 hectares).The Avars badly damaged the palace, but, when their incursion was over early in the 7th century the inhabitants of the nearby ruined city of Diocletian’s birthplace Solin took refuge within what remained of the palace and built their homes, incorporating the old walls, columns, and ornamentation into their new structures. Today this area now comprises the nucleus of the “old town” of Split and Solin has become Solona part of the metro area of Split the largest Croatian city on the coast.The Palace is built of white local limestone and marble of high quality, most of which was from Brač quarries on the adjacent island of Brač which also supplied the stone used to build the White House in the USA. The Palace was decorated with numerous 3500 year old granite sphinxes, originating from the site of the great Egyptian Pharaoh Thutmose III (1479 BC to March 11, 1425 BC) who conquered the Phoenician cities in Syria. Only three have survived the centuries.Diocletian was born near Salona in Dalmatia , some time around 244. The first time Diocletian’s whereabouts are accurately established, in 282, he had been apponted by the newly Emperor Carus to be commander of the Protectores domestici, the élite cavalry force directly attached to the Imperial household – a post that earned him the honor of a consulship in 283. During the withdrawal from Persia Carus’s son now the Roman Emperor Numerian, died suspiciously in his sealed carriage. The suspicion of murder evidently arose because the ambitious Aper had attempted to conceal the fact of Numerian’s death while he prepared the ground for his own accession to the Purple. Diocles, commander of the Domestici describes the early proof of Diocletian’s capacity for ruthless and decisive action that was to distinguish him as the Emperor.

On 20 November 284, the army of the east gathered on a hill 5 kilometres outside Nicomedia. The army unanimously saluted Diocles as their new augustus, and he accepted the purple imperial vestments. He raised his sword to the light of the sun and swore an oath disclaiming responsibility for Numerian’s death. He asserted that Aper had killed Numerian and concealed it. In full view of the army, Diocles drew his sword and killed Aper. According to the Historia Augusta, he quoted from Virgil while doing so and thus giving him no chance to Aper to justify himself or, perhaps, implicate anyone else. Soon after Aper’s death, Diocles changed his name to the more Latinate “Diocletianus”, in full Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus

Most officials who had served under Carus in Rome retained their offices under Diocletian. In spite of his failures, Diocletian’s elevation of Bassus as consul symbolized his rejection of Carus’ government in Rome, his refusal to accept second-tier status to any other emperor, and his willingness to continue the long-standing collaboration between the empire’s senatorial and military aristocracies. It also tied his success to that of the Senate, whose support he would need in his advance on Rome.

Following the precedent of Aurelian (A.D.270-275), Diocletian transformed the emperorship into an out-and-out oriental monarchy. Access to him became restricted; he now was addressed not as First Citizen (Princeps) or the soldierly general (Imperator), but as Lord and Master (Dominus Noster) . Those in audience were required to prostrate themselves on the ground before him.

Diocletian established the Tetrarchy a new system for the first time divided rule of the empire into the Western and Eastern courts, each headed by a person with the title of Augustus. Each of the two Augusti also had an appointed successor, a Caesar, who administered about half the district belonging to his own Augustus (and was subordinate to him). In Diocletian’s division, Dalmatia fell under the rule of the Eastern Court, headed by Diocletian, but was administered by his Caesar and appointed successor Galerius, who had his seat in the city of Sirmium. In AD 395, the Emperor Theodosius I permanently divided Imperial rule by granting his two sons the position of Augusti separately in the West and the East. This time, however, Spalatum and Dalmatia fell under the Western Court of Honorius, not the Eastern Court.

|

Even the most skeptical among Rome’s intellectual elite saw religion as a source of social order. By the height of the Empire, numerous international deities were cultivated at Rome and had been carried to even the most remote provinces, among them Cybele, Isis, gods of solar monism such as Mithras and Sol Invictus, are found as far as Roman troops ventured including Roman Britain. Because Romans had never been obligated to cultivate one god or one cult only, religious tolerance was not an issue in the sense that it is for competing monotheistic systems. Diocletian built temples for Isis and Sarapis at Rome and tended to favor gods who would best promote unity of the whole empire, instead of more local deities. In Africa, Diocletian’s revival focused on Jupiter, Hercules, Mercury, Apollo and the Imperial Cult where he invested heavily in temples. Diocletian when restoring the Curia at Rome’s Forum recognized Mithras as the patron deity of the Roman Empire in the bases of a triumphal imperial monument.

Diocletian returned to his Eastern capital Antioch [ Antakya,Turkey today] in the autumn of 302. Diocletian with his junior-emperor and son-in-law believed that the deacon Romanus of Caesarea was arrogant for interrupting Roman sacrifices and Diocletian had his tongue tore out and executed. Soon after he left the city for his Eastern capital of Nicomedia accompanied by Galerius with whom he argued over imperial policy towards Christians. Diocletian argued that forbidding Christians from

|

|

| Diocletian argued that forbidding Christians from the bureaucracy and military would be sufficient to appease the gods, but Galerius, his junior-ruler and commander of the Eastern Army pushed for extermination. The two men sought the advice of the oracle of Apollo at Didyma. The oracle responded that the impious on Earth hindered Apollo’s ability to provide advice. At the behest of his court, Diocletian acceded to demands for universal persecution. |

the bureaucracy and military would be sufficient to appease the gods, but Galerius pushed for extermination. Diocletian, for all his religious conservatism, still had tendencies towards religious tolerance. Galerius, by contrast, was a devoted and passionate pagan. According to Christian sources, he was consistently the main advocate of such persecution. He was also eager to exploit this position to his own political advantage. As the lowest-ranking deputy emperor of the four in Diocletian’s tetrarchic system Galerius was always listed last in imperial documents. Until the end of the Persian war in 299, he had not even had a major palace.

On 23 February 303, Diocletian ordered that the newly built church at Nicomedia be razed. He demanded that its scriptures be burned, and confiscated its valuables for the treasury. The next day, Diocletian’s first “Edict against the Christians” was published The edict ordered the destruction of Christian scriptures and places of worship across the empire, and prohibited Christians from assembling for worshipThe two men sought the advice of the oracle of Apollo at Didyma The neoplatonic philosopher Porphyry may also have been present at this meeting. Upon returning, the messenger told the court that “the just on earth” hindered Apollo’s ability to speak. These “just”, Diocletian was informed by members of the court, could only mean the impious Christians on Earth were responsible for hindering Apollo’s ability to provide critical advice. At the behest of his court, Diocletian acceded to demands for a universal persecution

Although further persecution edicts followed, compelling the arrest of the Christian clergy and universal acts of sacrifice, the persecution edicts were ultimately unsuccessful; most Christians escaped punishment, and pagans too were generally unsympathetic to the persecution. Western Europe in particular tempered by a different set of Roman Emperors showed little enthusiasm towards persecution. The martyrs’ sufferings strengthened the resolve of their fellow Christians. On the other hand, Manichaeism, Christianity’s greatest rival at the time, was also targeted by Diocletian even more ruthlessly and never recovered.

Diocletian, like Augustus and Trajan before him, styled himself a “restorer”. He urged the public to see his reign and his governing system, the Tetrarchy (rule by four emperors), as a renewal of traditional Roman values and, after the anarchic third century, a return to the “Golden Age of Rome”. As such, he reinforced the long-standing Roman preference for ancient customs and Imperial opposition to independent societies. From 250 to 300 the Christian community had grown from a population of 1.1 million to 6 million or about 10% of the empire’s total population and this also included the wealthy and influential.

Within twenty-five years of the persecution’s inauguration, the Christian Emperor Constantine would rule the empire alone. Under Constantine’s rule, Christianity would become the empire’s preferred religion. Constantine the Great (Roman Emperor from 306 to 337 AD of Thracian-Illyrian ancestry.) after his father’s death in 306 AD, Constantine emerged victorious in a series of civil wars against the emperors Maxentius and Licinius to become sole ruler of both west and east by 324 AD. The age of Constantine marked a distinct epoch in the history of the Roman Empire. He built a new imperial residence at Byzantium and renamed the city Constantinople. Constantine played an influential role in the proclamation of the Edict of Milan, which decreed tolerance for Christianity in the empire. He called the First Council of Nicaea in 325, at which the Nicene Creed was professed by Christians

Diocletian was demonized by his Christian successors: Lactantius intimated that Diocletian’s ascendancy heralded the apocalypse, and in Serbian mythology, Diocletian is remembered as Dukljan, the adversary of God. The persecution which was primarily carried out in the East caused many churches to split between those who had complied with imperial authority (the traditores), and those who had remained “pure”. Some historians claim that Christians created a “cult of the martyrs”, and exaggerated the barbarity of the persecutory era.

While Diocletian soon saw his tetrarchic system collapse under Constantine’s consolidation of power and Christianity Once he retired, however, Under the Christian Constantine, Diocletian may have been maligned but he validated Diocletian’s achievements and the autocratic principle he represented: the borders remained secure, in spite of Constantine’s large expenditure of forces during his civil wars; the bureaucratic transformation of Roman government was completed; and Constantine took Diocletian’s court ceremonies and made them even more extravagant.

Diocletian’s reforms fundamentally changed the structure of Roman imperial government and helped stabilize the empire economically and militarily, enabling the Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire until 1453 and existing Roman Empire to remain essentially intact for another hundred years despite being near the brink of collapse in Diocletian’s youth. Weakened by illness, Diocletian left the imperial office on 1 May 305, and became the first Roman emperor to voluntarily abdicate the position. He lived out his retirement in his palace on the Dalmatian coast, tending to his vegetable gardens. His palace eventually became the core of the modern-day city of Split.

Around AD 639 the hinterland of Dalmatia fell after the invasion of Avars and Slavs, and the city of Salona was sacked. The majority of the displaced citizens fled by sea to the nearby Adriatic islands. Following the return of Byzantine rule to the area, the Roman population returned to the mainland under the leadership of the nobleman known as Severus the Great. They chose to inhabit Diocletian’s Palace in Spalatum, because of its strong fortifications and defendable setting. The palace had been long-deserted by this time, and the interior was converted into a city by the Salona refugees, rendering Spalatum the effective capital of the Province.

Throughout the following centuries, effectively until the early 13th century and the Fourth Crusade, Spalatum would remain a possession of the Byzantine emperors, even though its hinterland would seldom be under Byzantine control, and de facto suzerainty over the city would often be exercised by Croatian, Venetian, or Hungarian rulers. Overall, the city enjoyed significant autonomy during this time, due to the periodic weakness and/or preoccupation of the Byzantine Imperial administration.

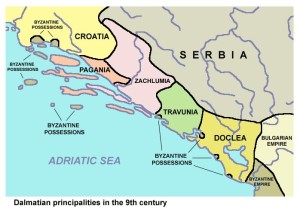

Following the great Slavic migration into Illyria in the first half of the 6th century, Dalmatia became distinctly divided between two different communities: The hinterland populated by Slavic tribes – which were roughly Croats to the north and Serbs to south, separated by the Cetina river. There were also the Romanized Illyrian natives, and Celts in the north.

The Byzantine enclaves populated by the native Romance-speaking descendants of Romans and Illyrians (speaking the Dalmatian language), who lived safely in Ragusa, Iadera, Tragurium, Spalatum and some other coastal towns, like Cattaro (Kotor). These towns remained powerful because they had attained a greater level of civilization, had better fortifications and retained their connection with the Byzantium economy. The Slavs were, at the time, just undergoing the first steps of becoming Christianized. The different communities were frequently hostile at first.

The establishment of cordial relations between the cities and the Croatian dukedom began with the reign of Duke Mislav (835), who signed an official peace treaty with Pietro, doge of Venice in 840 and who also started giving land donations to the churches from the cities.

As the Littoral Croatian Duchy became a Kingdom after 925, its capitals were in Dalmatia: Biaći, Nin, Split, Knin, Solin and elsewhere.the Croatian kings exacted tribute from the Byzantine cities, Tragurium, Iadera and others, and consolidated their own power in the purely Croatian-settled towns such as Nin, Biograd and Šibenik.

As the Dalmatian city states gradually lost all protection by Byzantium, being unable to unite in a defensive league hindered by their internal dissensions, they had to turn to either Venice or Hungary for support. Each of the two political factions had support within the Dalmatian city states, based mostly on economic reasons.

The Venetians, to whom the Dalmatians were already bound by language and culture, could afford to concede liberal terms as its main goal was to prevent the development of any dangerous political or commercial competitor on the eastern Adriatic. The seafaring community in Dalmatia looked to Venice as mistress of the Adriatic. In return for protection, the cities often furnished a contingent to the army or navy of their suzerain, and sometimes paid tribute either in money or in kind. Arbe (Rab), for example, annually paid ten pounds of silk or five pounds of gold to Venice.

The doubtful allegiance of the Dalmatians tended to protract the struggle between Venice and Hungary,

During the Venetian rule in Dalmatia from 1420 to 1797 the number of Orthodox Serbs in Dalmatia was increased by numerous migrations.

An interval of peace ensued, but meanwhile the Ottoman advance continued.Hungary was itself assailed by the Turks, and could no longer afford to try to control Dalmatia. Christian kingdoms and regions in the east fell one by one, Constantinople in 1453, Serbia in 1459, neighbouring Bosnia in 1463, and Herzegovina in 1483. Thus the Venetian and Ottoman frontiers met and border wars were incessant.

Later in 1797, in the treaty of Campo Formio, Napoleon I gave Dalmatia to Austria in return for Belgium. The republics of Ragusa (Dubrovnik) and Poljica retained their independence, and Ragusa grew rich by its neutrality during the earlier Napoleonic wars. By the Peace of Pressburg in 1805, Istria, Dalmatia and the Bay of Kotor were handed over to France.

In 1806, the Republic of Ragusa (Dubrovnik) finally succumbed to foreign (French) troops under general Marmont, the same year a Montenegrin force supported by the Russians tried to contest the French by seizing Boka Kotorska. The allied forces have pushed the French to Ragusa. The Russians induced the Montenegrins to render aid and they proceeded to take the islands of Korčula and Brač but made no further progress, and withdrew in 1807 under the treaty of Tilsit. The Republic of Ragusa was officially annexed to the Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy in 1808.

The Austrian Empire declared war on France in 1813, restored control over Dalmatia. The Habsburg Empire had its own agenda in Dalmatia, that opposed the formation of the Italian state in the Revolutions of 1848 in the Italian states, but supported the development of Italian culture in Dalmatia, maintaining a delicate balance that primarily served its own interests. At the time, the vast majority of the rural population spoke Croatian while the city aristocracy spoke Italian. The Italian-leaning high society promulgated the idea of a separate Dalmatian national identity under the multi-ethnic Austro-Hungarian monarchy

In World War I, Austria-Hungary was defeated and it disintegrated, which helped solve the internal political conflict in Dalmatia.In April 1941, during World War II, the Axis powers invaded and conquered Yugoslavia. Many Croats from Dalmatia joined the resistance movement led by Tito’s Partisans, while others joined the fascist Croatia of Ante Pavelić. The result was a terrible guerrilla war that ravaged all Dalmatia.

After 1945, most of the remaining Italians fled the region. The “disappearance” of the Italian speaking populations in Dalmatia was nearly complete after World War II. After the World War II, Dalmatia was divided between three republics of socialist Yugoslavia – almost all of the territory went to Croatia, leaving Cattaro Bay of Kotor to Montenegro and a small strip of coast at Neum to Bosnia-Herzegovina.

In 1990, when Yugoslavia began to disintegrate, Croatian leadership announced their intention to declare independence in 1991, Northern Dalmatia, where there lived a significant population of Serbs rebelled, under encouragement and with assistance from a variety of Serbian nationalist circles, Major bases, commanded by die-hard officers and manned by reservists from Montenegro and Serbia, became the object of standoffs that usually ended with JNA personnel and equipment being evacuated under supervision of EEC observers

The war suffering in Dalmatia was among the highest compared to the other Croatian regions, particularly in the Dalmatian hinterland, where much of the infrastructure was ruined. The tourism industry – previously the most important source of income – was deeply affected by negative publicity and didn’t properly recover until the late 1990s.

Croatia is the last nation to become a member of the European Union in 2013. The national parks and nature parks are still in early stages of developing tourism infrastructure. The tradition of annual arts festivals continues to grow and build on some world class drama, film and music festivals begun in the 1960s. During the economic expansion of the 1960s, work began on building many tourism facilities: hotels, marinas, campsites and even entire tourist villages, mainly on the Adriatic, but also inland but much of this is small scale. Campgrounds and individual homes will continue to play a large role in Croatian tourism for the indefinite future.

The surge in Croatian tourism growth following the conflicts in the wake of Yugoslavian dissolution into seven nations in 1990 began in 1996, and especially after 2000 when Croatia itself was placed at the peak of tourism in the world with a surge of discovery articles that continues to build many years hence.

Croatia has been a leading supporter of festival arts as both a way to generate tourism and promote cordial relations with its neighbors. In 2015 the premier resort town of Bol, on the island of Brac between Split and Hvar island. will host the 3rd Croatian host or Carnival Capital for the XXXV FECC Carnival Cities Convention. FECC-Croatia has taken a leadership role in the world’s only organization dedicated to the preservation and promotion of annual Carnivals or Federation of European Carnival Cities Croatia has been rewarded with an explosion of annual new and restored Carnival celebrations throughout the Balkans. The former Yugoslavian citizen neighbors and other FECC members provide mutual support and exchange of Carnival performing parade groups to make their events bigger and better. The Carnival spirit, or this intangible culture of looking forward to a harmonious embrace of all in a collective celebration of joy and creativity in the present is very much alive in Croatia and all its surrounding neighbors. There is still time for the rest of the Mediterranean and the world